- SPAB report from 1882

- The remaining evidence

- Background

- Fitting the pieces

- Church Buildings Council Comments

- Footnotes

- Further reading

SPAB report from 1882

In 1882 the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings visited Deopham and produced a report on the state of the church – this is available in full here. Concerning the screens, they reported as follows:

There are some extremely interesting screens …

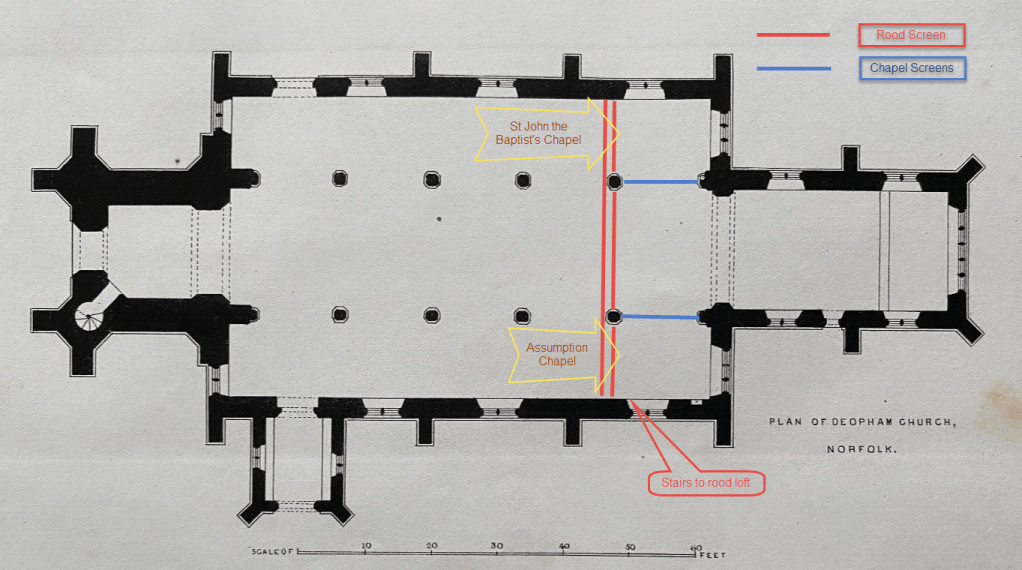

The Chancel extended originally one Bay into the Nave, and here there were Screens, extending the whole width of the Church, with a rood-loft at the top – the Stairs to which are in the S. wall of the S. Aisle. Of these 3 screens only a part, on the north side, remains: this eastern bay, screened off thus from each of the Aisles, formed a little Chapel, the side screens of which, each with a door in it, remain….

The Colouring on the remaining parts of the Screens is exceeding delicate and beautiful: the colour is on both sides of the Screens.

It is interesting to note that at the time of this report:

– the screens were still sufficiently intact to have doors;

– the chapels extended one bay into the nave (see below);

– the pieces of the screens that remained were still in situ;

– the rood was accessed by stairs in the south aisle (see below).

The SPAB report also commented disapprovingly on the vicar’s desire to repurpose these screens as some form of division across the chancel.

The remaining evidence

Panel 1

Location: Leaning against south wall near entrance

Dimensions: 2,440 mm wide, 1,270mm high. The sill is 2,440mm long.

The directories from 1864 and 1890 state that at that time there were still “remains of painted screens at the east ends of the aisles”.

Photo: G Sankey, Feb 2023

Detail of right hand section of panel 1:

Photo: G Sankey, Feb 2023

Reverse side of part of panel 1:

Photo: G Sankey, Feb 2023

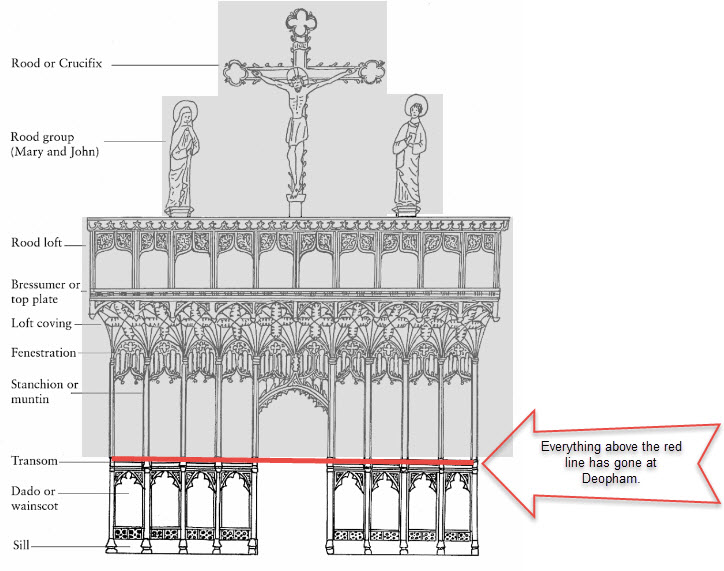

Where once this panel would have risen gracefully towards the rafters, it has subsequently been hacked off. Nothing is left in this church of the higher structure:

Photo: G Sankey, Feb 2023

Photo: G Sankey, Feb 2023

This broken piece of tracery propped against the wall alongside the large piece pictured above does not fit any of the panels remaining in the church. It is however the same design.

Panel 2

Location: Used as a divider between the “vestry” behind the organ and the south aisle altar.

Dimensions: 2,500mm wide, 1,287mm high.

Photo: G Sankey, Feb 2023

Photo: G Sankey, Feb 2023

Panel 3

Location: Leaning against east end of south wall.

Dimensions: 895mm wide; 1,165mm high but appears to have lost its sill.

The absence of tracery on this panel has given rise to the possibility that this panel might have come from a different church, or at the very least from a separate part of the overall structure. See further in extract from letter below.

Photo: G Sankey, Feb 2023

The rear of panel 3:

Photo: G Sankey, Feb 2023

Altar Table

Location: East end of south aisle.

Dimensions of tracery: each of the side panels is 780mm high x 530mm wide. The top panel is 285mm high; the bottom section is 225mm high.

It has been suggested that the tracery in the south aisle altar table was sourced from the medieval screens. This is mentioned in a description from 1851 of the village school’s opening ceremony, which says that at that time the “altar table has just been made” using fragments of the screen.

Certainly the top and bottom panels at each side are ancient, but there is no trace of the medieval paint that is so prominent on the other panels. The two vertical pillars appear much more recent than the carving in the panels at the top and bottom. The letter below from the Church Building Council suggests that these pieces could even have come from another church.

Photos: G Sankey, March 2023

Stairs to the rood loft

These stairs were part of the access to the rood loft which ran all the way along the top of the screen. There is more about this below.

Photo: G Sankey, Feb 2023

Markings on the stone pillars

Photo: G Sankey, Feb 2023

A slot has been cut into the east side of the north east pillar to a height of 2.88m

Photo: G Sankey, Feb 2023

A slot has been cut into the east side of the south east pillar to a height of 3.1m.

Photo: G Sankey, Feb 2023

A slot has been cut into the west side of the northern chancel arch to a height of 1.22m.

The frieze around the top of the south east pillar has been cut back on the north and west faces.

Photo: G Sankey, Feb 2023

Background

Purpose of the Rood Screens

Nicholas Orme has written as follows concerning medieval church culture:-

Church leaders urged congregations to view and venerate the supreme moment in the mass: the ‘elevation’ at which the priest held up the the bread and wine now transformed into the body and blood of Christ, hence the need for maximum visibility from the nave. At the same time the holiness of the consecration, with its manifestation of Christ in a physical sense, required the mass to be done in a holy and secluded space. Accordingly a screen of stone or wood was erected between the chancel and the nave … called the pulpitum and in modern English the ‘rood screen’.

The ‘rood’ was the cross, bearing the crucified Christ, which stood above the screen, flanked by statues of the Virgin Mary to the north and St John the Evangelist to the south, as they were imagined to have been at the crucifixion.1

As well as a barrier, the rood loft was used:-

- so that the acolyte or attendant having charge of these things might trim the lamps, light and extinguish the tapers, deck the images with garlands on feast days, and shroud them with veils in Lent.2

- for the performance of miracle/mystery plays;

- for the priest to address the congregation (before there was a stand-alone pulpit);

- for minstrels – both vocal and instrumental.

The Chapels

The Assumption Chapel and St. John’s Chapel would have been maintained by the corresponding guilds who would have funded the performance of masses for their deceased members and the provision of candles to ensure that there were always lights in these chapels.

Destruction of the Screens

When Henry VIII separated the English church from Roman Catholicism in 1534, there was much destruction of artefacts, symbols and books considered to be part of the papal legacy. However, although there was much defacing of images of the saints, many items were removed from churches but not actually destroyed. They were stowed away in barns and attics.

This process continued under the reign of Edward VI (1547 – 1553).

When the the Catholic Queen Mary came to the throne in 1553, the hidden items were brought back into use.

When the Protestant Elizabeth I came to the throne, she yet again reversed policies of her predecessor and reinstated Henry VIII’s edicts. In 1559 she issued a series of injunctions for “the suppression of superstition” and “to plant true religion“.

Commissioners were sent out to ensure the total destruction of all equipment of Catholic worship. This purge carried on for several years and was referred to as “the tyme of the defacinge of all papistrie“3. This time, the destruction was total. There was no hiding of anything – the commissioners wanted proof that all artefacts had been destroyed.

Article XXIII of these injunctions stated uncompromisingly:-

Also, that they shall take away, utterly extinct, and destroy all shrines, coverings of shrines, all tables, candlesticks, trindals, and rolls of wax, pictures, paintings, and all other monuments of feigned miracles, pilgrimages, idolatry, and superstition, so that there remain no memory of the same in walls, glass windows, or elsewhere within their churches and houses; preserving nevertheless, or repairing both the walls and glass windows; and they shall exhort all their parishioners to do the like within their several houses.

One instance in Yorkshire where concealment was attempted resulted in the offenders being required to do public penance barefoot in white sheets at the main Sunday service, and to make a public confession that they had “conceyled and kepte hyd certane Idoles and Images undefaced and lykewise certain old papisticall bookes in the Latyn tonge… to the high offence of Almighty God the breache of the most godly lawes and holsome ordinances of this realme the greate daunger of our owne sowles and the deceaving and snarring of the soules of the simple“. They were then required to burn the images in the presence of residents of the parish at the church gate, and the performance of their penance was to be certificated to the commissioners.4

It would have been during this period starting in 1559 that the Deopham Rood Screen was cut down to the height of the fragments remaining, although these fragments may have remained in their historical position. The fact that the Deopham panels have no images of saints would have given them some respite. The wall paintings would have been whitewashed.

Fitting the pieces

There would have been two elements to the screens at St. Andrew’s Deopham:-

1. The rood screen running from south to north which would have divided the full width of the church (as is the case with the reinstated screen at Attleborough – see adjoining photo).

There would have been openings in these screens to allow passage between the nave and the chapels and the chancel for processions as well as general movement.

Photo: G. Sankey, March 2023

2. The screens running east to west that divided off the two side chapels.

These are shown in the following plan:-

The rood screen itself looking from the back of the church towards the altar would have contained the elements shown in the drawing below by Lucy Wrapson5. The panels that remain have been cut off just above the transoms. The screen at Deopham would have been much wider than shown in this schematic.

It would appear futile to take the distances between the stonework to calculate the number of panels and therefore exactly how the surviving panels fit together. This detail from St Edmund’s Acle shows that the panels could be cut off to make them fit rather than being constructed to occupy the space available!

Photo: Simon Knott,

NorfolkChurches.co.uk

Church Buildings Council Comments

In a letter dated October 26th 2017 Janet Berry, the Head of Conservation at the Church Buildings Council, wrote as follows:-

There are currently 3 painted dado screens, a loose painted piece of tracery, and some unpainted tracery that has been re-used in an altar in the church. One dado section, consisting of 3 ½ panels, has been re-used as a divider in the south transept. It has had half of the right hand panel cut off to fit tightly against the wall as the divider. Another 2-panel dado section is resting against the wall close by. This section does not have any tracery (nor evidence of such), as do the other panels, and therefore may not be from the same section of screen as the other pieces; however it has a closely related decorative scheme, and is probably from the same church. Another 3-panel section is currently resting against the south wall, the lower transom of which extends out to the left (but in a fragmented state), and with the small piece of loose tracery resting against it. This section has very similar decoration and tracery to the piece being used as a divider, and therefore is very likely to be part of the same original screen. The small piece of painted tracery is similar in design and colouring to the tracery on the 3-panel sections, but there is no tracery missing from these pieces.

It therefore appears that there are 4 distinct screen sections, 3 of which may be from the same screen (but none of which fit obviously together), plus one piece from a different but similarly decorated screen. There are also two pieces of unpainted tracery that have been used as part of an altar table, presently in front of the re-used divider. The carving and proportions of this tracery look similar to the tracery elements in the two larger screen sections, so may have survived from other parts of this screen, or may be from a different church.

There was a discussion at the site visit on what to do with all the pieces. It is clear that there are pieces of at least two original screens in the church (and possibly fragments from other churches). The two largest screens are apparently too long to fit across the nave, if positioned symmetrically, which is the usual place for a rood screen. They may however have been used to separate the chancel and transepts (“parclose screens”, as found at Southwold, St. Edmund, and Clare, Ss Peter & Paul, for example), although further research would be needed to confirm this hypothesis. In summary, it is not clear where the screens would have originally been placed, and so there is not enough evidence at the moment as to where they should be re-positioned. There is documentary reference to screens in this church, in a will of 1488.

Where the author says that “The two largest screens are apparently too long to fit across the nave, if positioned symmetrically, which is the usual place for a rood screen” she must mean “fit across the chancel arch“. There is plenty of room for them to fit across the nave in the position shown in the plan above.

Footnotes

- Nicholas Orme, Going to Church in Medieval England, Pg 94 ↩︎

- Bond and Bede Roodscreens and roodlofts, Vol I, Pg 85. ↩︎

- Eamon Duffy, Stripping of the Altars, Pg 574 ↩︎

- Eamon Duffy, Stripping of the Altars, Pg 570 ↩︎

- Lucy Wrapson, East Anglian medieval church screens: a brief guide to their physical history in Hamilton Kerr Institute – Bulletin Number 4, pg 34. ↩︎

Further reading

- https://www.hki.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/projects/roodscreens

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2022/03/15/norfolk-rood-screens/

Contains a useful bibliography - C.E. Keyser, A list of buildings in Great Britain and Ireland having mural and other painted decorations, of dates prior to the latter part of the sixteenth century, with historical introduction and alphabetical index of subjects.

Records in his only comment on Deopham: “Back of screen: foliated diaper”. - A full text of all the injunctions can be found here:

https://history.hanover.edu/texts/engref/er78.html

| Date | Change |

|---|---|

| 26/2/24 | Notes from SPAB report |

| 16/6/23 | Added link to the page concerning gilds |

| 8/3/23 | Published |