Contents

Deliveries

Fred Bales

Fred Bales started a coal delivery round based at the cottage which used to stand opposite Old Man’s Farm on the road to Hingham out of Deopham.

Fred Bales’ wife used to feed the horse (Nobby) at 5 a.m. before Fred Bales assisted by Reggie Leegood did the delivery rounds. The coal was fetched from Kimberley railway station, generally after finishing supper.

Photo: G. Sankey, February 2025

The following image shows the site of the cottage from which coal was distributed.

Photo: G. Sankey, February 2025

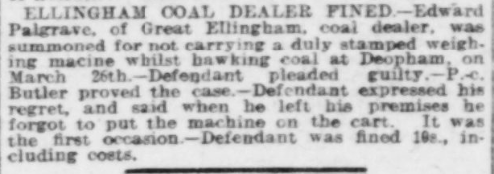

Outsiders: The following report appeared in the Downham Market Gazette published on 06 April 1912

© THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

When Fred Bales moved to Ivy Farm in Deopham Green in 1939, he brought the coal business with him despite also running a substantial farm. He and Reggie Leegood were running two horses, each with a four wheeled trolley. As well as domestic coal, they were also delivering coal graded for the steam engines used for thrashing.

Fred Bales’ son Gordon has retained some of the brass bosses from the wheels of the trollies that were used for delivering coal.

Photo: G. Sankey, March 2025

Running the farm of over 100 acres as well as the coal business was a challenge. Eventually Fred Bales sold the business.

Mrs. Riseborough

Mrs Riseborough bought the business from Fred Bales and employed Charlie Wells to carry out the deliveries. They were based in Hingham.

Charlie Wells is remembered as the founder of C.C. Wells of Norfolk, a significant supplier of fruit and veg in the area, with regular market stalls.

Arthur Patrick

Arthur Patrick, assisted by his sons, ran the business from a site in Victoria Lane.

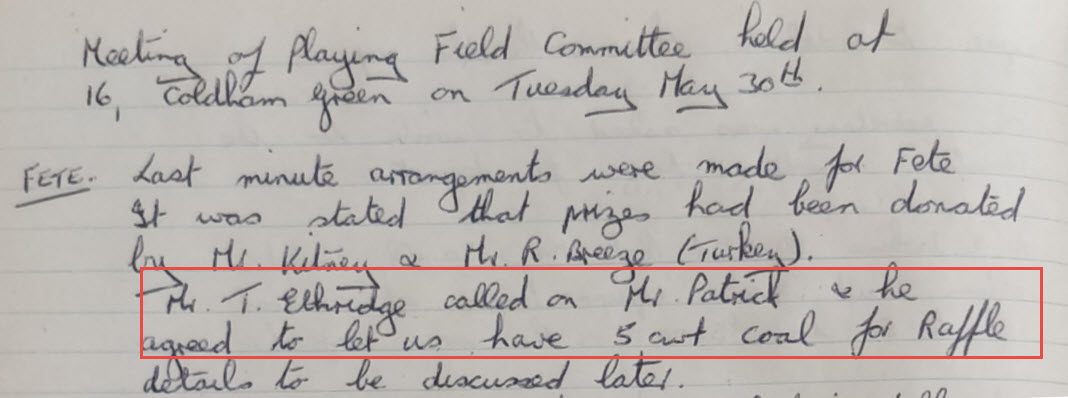

The Patricks donated a bag of coal to the Playing Field Committee for their fund raising, as recorded in this page from their minutes for the meeting of May 30th 1972:

Fuel Allotment Charity of Deopham

There is an article on the Fuel Allotment Charity here.

Coal Mining in Deopham

The 1894 Copyhold Act gave Copyhold tenants the right to buy out their copyhold obligations and turn their property into a freehold asset. This process was known as Enfranchisement. This Act allowed the Lords of the Manors to retain rights to mining and extraction of minerals etc. Most of the Deopham enfranchisements did not take advantage of this and explicitly excluded “Section 23” of the Act.

The Ecclesiastical Commissioners (who had taken over from the Dean & Chapter of Canterbury as Lords of the Manor of Deopham in 1862) invoked their rights under this law to retain the entitlement to extract what was under the ground, specifically listing coal.

One such enfranchisement deed was that of James Oakley in 1909, whose agreement included the following:

Except and reserved unto the Lords, their successors and assigns all mines, beds and veins of minerals, coal, clay, plate, stone and other substances and substrata within and under the hereditaments hereby granted, or any part thereof, lying below a distance of Two hundred feet from the surface thereof.

This land is now known as Walnut Tree Farm.

Another enfranchisement where the Ecclesiastical Commissioners retained similar mining rights was that of Thomas Frederick Ringer, also signed in 1909, which included a paragraph similar to that of James Oakley reproduced above, with the following additional paragraph:

Together with full power to win and work, get and carry away by any methods of mining which shall for the time being be in ordinary use in the District or otherwise recognised as a proper way of working mines, but without entering upon the surface of the said hereditaments or of the buildings for the time being thereon.

This land is close to the Stalland.

A more extensive description of reservations for Mines and Minerals in Deopham is available here.

Coal in Norfolk

The following article appeared in the Diss Express published December 4th 1891.

THE PROBABILITY OF FINDING COAL IN EAST ANGLIA

On Monday night, Dr. J. E. Taylor, curator of Ipswich Museum, gave a lecture upon this subject before a large audience at the Atheneum, Bury St. Edmund’s. The Earl of Cadogan presided. After some preliminary remarks the lecturer directed attention to an artesian well boring made at Harwich in 1859, by Mr. Peter Bruff, of Ipswich. That well had a depth of less than 1200 ft., but the lower carboniferous rocks were struck and penetrated to a depth of 70 feet. He pointed out, however, that these were not the real coal-bearing rocks, and that every foot deeper they went down at Harwich took them further away from the proper position where the coal-bearing strata would be found. The one important fact to geologists in connection with the Harwich well-boring was that none other of the secondary formation was present here with the chalk, but that the chalk become bang down [sic] upon the old floor of primary rocks. Reasoning on this point, and believing that to the North the upper coal measures – the higher coal measures that was to say – would be found in successive order, he had thought that trial borings to the north in Suffolk, and possibly to the in south in Essex, might penetrate some of the upper measures containing the narrow and elongated coal fields he had referred to.

A few years ago at Combs, near Stowmarket, the chalk was pierced in a deep well at a considerable less depth than had been anticipated – a little under 900 feet – but unfortunately the boring tool did not proceed any further, so that geologists were left in darkness as to what remained underneath. The primary rocks in Suffolk had never really been bottomed until a few months ago, when at Culford, five miles from Bury St. Edmund’s, in an artesian well-boring upon Lord Cadogan’s Estate the chalk and the fen beds of the underlying cretaceous strata were passed through, and what were now believed to be the primary rocks were reached. These had only been pierced, however, for a distance of a few feet, and none of the characteristic fossils of the carboniferous formation hai been brought up. Still the bottom rocks at Culford were believed by Mr. A. Jukes-Brown to be primary, and Dr. Taylor expressed his conviction, from the microscopical examination he had made of a few fragments, that they were from the measures which might be expected to contain the coal seams. However, he hoped Earl Cadogan would come to the aid of scientific men and allow the boring to proceed another hundred feet. They must remember that this was the first time the underlying floor had been reached in Suffolk, and that a boring through these soft carboniferous shales might be of practical benefit even if coal were not found. He had submitted specimens of these soft shales to analysis by Mr. J. Napier, of the Ipswich Museum and Laboratory, and as he (the lecturer) anticipated they were found to contain traces of petroleum. It would not be a bad thing if a deep boring through these soft shales yielded petroleum instead of coal. What he should like to see was trial borings a little further to the north of Culford. Taking a line from Southwold, through Eye to Mildenhall, he thought that would be the best district over which to make such efforts to reach the upper measures which probably lie upon the northern flanks of these underground primary rocks.

He had much faith in the district of Brandon, Lakenheath, and Mildenhall, because the memoir of the geological survey, so carefully mapped and measured by Mr. Woodward, showed that the Oolitic rocks thinned out in that direction, and that very deep borings would not be required therefore in order to reach the primary rocks beneath.

In conclusion, Dr. Taylor gave fair warning that this idea was as yet in the experimental scientific stage – not in a commercial stage – but said that, seeing how coal has been discovered under similar circumstances elsewhere, he believed the inhabitants of East Anglia would have sufficient public spirit, not to sit with their hands in their laps, but to solve the problem once and for all by instituting trial borings in the places he had suggested.

| Date | Change |

|---|---|

| 14/4/25 | Mines & Minerals link |

| 18/3/25 | Published |