Contents

- Introduction

- Birth

- Move to Deopham

- Departure from Deopham

- Return to Peacocks

- 2001

- Death

- Footnotes

- Credits

- Bibliography

- Navigation

Introduction

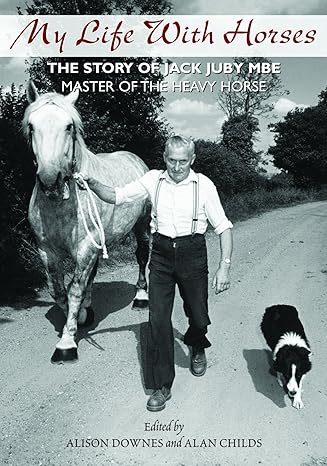

This page gives an outline of Jack Juby’s life, but in line with the subject of this website it is heavily biased towards his time in Deopham. His daughter’s biography (see below) fills in many of the gaps in the life of this well respected expert in Heavy Horses.

In common with other pages on this website, passages in black on white are direct quotations from the works cited.

Birth

John Juby was born on February 10th 1920 in Reymerston and baptised at the parish church on March 28th 1920. He was always known as Jack except on formal documents. He was the oldest boy and one of seven children. His father was a council roadman and his mother a midwife.

He attended school in Reymerston.

Move to Deopham

After school, Jack worked in Reymerston for Stanley Mortlock working with animals, and being involved in their transport.

Jack met his future wife, Margaret, when she was singing in the church choir at Reymerston and he was pumping the organ. She was working as a maid at Reymerston Hall. In the late 1930s, at the age of 16, he married Margaret when she was pregnant and continued to live with his parents in Reymerston for a while.

With thanks to Elaine Peacock for allowing sight of this photograph.

Geoffrey Peacock acquired a farm in Reymerston adjacent to the Juby’s home. He and Jack Juby came to know each other, and eventually Geoffrey Peacock suggested that Jack should come to Deopham to work for his father, William Liddelow Peacock.

William Peacock is featured in this photograph.

Early married life

Jack, Margaret and their baby Bryan moved into the left-most section of the High Elm cottages – shown in this photograph (at the junction between Pye Land and Vicarage Road, just opposite the Peacock’s farm, subsequently renamed Keeper’s Cottage). Jack referred to this as “High Tree Corner”.

Photo: Alison Downes1

Jack recalled the move …

… we put the bed on and bits and pieces somebody had found us. A couple of chairs somebody else had found us and we packed them on there. We put the pram on and we went back to Deopham – and that was when I moved into that little cottage. When I got there the only thing we ever bought brand-new was an oak gate-legged table.2

Jack’s daughter Alison commented:

Sparsely furnished the little cottage may have been, but it was a home of their own for the young parents. Margaret recalls how they had one candle to last them the week. This would be ‘nipped out’ as soon as possible, once the blazing wood fire had illuminated the room. The wood collected in an old pram was of course free, and helped to eke out the limited amount of coal they could afford each week.

Bringing up baby

There was concern that baby Bryan was not getting enough sustenance; the “father” in this quote refers to Jack’s father.

He started giving him a little bread and sop – which was when mother [i.e. Jack’s mother] used to cube up dried bread and pour boiling water over it, then drain off the water and put in some butter and salt and pepper. Father used to sit with this baby on his lap ‘cos he was only little, and he put a little of this sop on a spoon. That’s what father used to do twice a day for weeks! Then when we put him to bed, you had a boiled sweet tied up in a bit of rag and pinned it on his chest and he used to lay and suck it but he couldn’t swallow it, could he? That was a regular thing that was, then.

The crusts left from scooping out the bread for the “sop” were filled with cheese and a pickled onion to make Jack’s lunch.

The Union

When Jack started to work full time, his wage was 30 shillings a week which was the standard rate set by the Agricultural Wages Committee; over the next few years the Union won a few increases for its members. Although he was a union member, like his father before him, he was not involved in strikes “and that sort of thing”.

I never did believe in that. That was a poor answer I think, but I also stuck to the Union. I have been a life member since I was 60 a free life member. Because father was a staunch union man he put us boys in the Union as soon as we earned money, so we kept it up like that. My argument is, I didn’t demand one and sixpence rise in that year. I didn’t go to the fight and argue – because we daren’t. So the Union got us that didn’t they? That was my Union that got us three and sixpence rise later on, and that hour off a week. My respect for the Union is because we weren’t strong enough or brave enough to do it ourselves. But in regards to these strikes they make me sick! That isn’t the answer. There’s a compromise somewhere, isn’t there?3

Beware the boss

Jack described the early warning system that was used by the men working for William Peacock:

We’d all be in a gang knocking these beet up. There’d be five or six of us pulling the beet, knocking them and laying them in rows. When the mould come off then they would come along and take the tops off the sugar beet and we’d be a-talking. All of a sudden the governor come across. The little old white spotted dog, a little old terrier, she used to be a god-send to us. The governor used to walk across the whole farm. He used to have gaps in the hedges where he’d come across. But Tiny, she’d allus come through the hedge first and she’d be a-barking, ‘Look out, Look out!’ The old man could see you, so you wouldn’t be talking too much then. While he was about you’d keep going. I’m talking about 1940, not 1840!

He’d come through the field where we were carting sugar-beet. As we were filling our carts, he would come strolling in there with his little old dog. He’d say, ‘I had a letter from the factory this morning, wanted to know if I had sold all my cows’. Then off he’d go. He meant, we were leaving too many leaves on the sugar-beet!4

Hard work

The following extract is taken from a letter he wrote to his sister, Hilda, not long after starting in Deopham. It gives an idea of his working day:

I really have been very busy. Wegg has left, so I have been team-man for a month till another man come, and have been up and into the stables every morning before five o’clock, till seven. Twenty minutes for breakfast and then tractoring till six and seven at night and then feeding the horses by lamp light after tea. Both the old man and the two sons, G. and P. [Geoffrey & Percy] all told me I improved the horses greatly after the first few days. You can bet I did too. I spent a good many hours combing and brushing them, I can tell you, and I used to think something of myself when I was using them, as I was head-man then, and the second horseman was the man that has been here 40 years. I had the two best horses in the stable, which nobody only the head-man is allowed to use, so I have been knocking up about 35/- a week now.5

Jack complained in this letter of suffering from “backache, headache, heartburn and altogether B— rotten”. He is reported by his daughter to have tackled the heartburn by “getting a piece of chalk out of a clay lump wall with his knife, and sucking that all day. Doctors were not troubled needlessly, so improvised cures had to be found”.

Milking

Jack made the following comments on milking, a job he was clearly good at:

When I got to Deopham, there I could milk 22 cows morning and night for the old man, (Lidlaw [sic] Peacock) by hand. He used to come up to the house and he’d have big old aluminium pails and you’d have your milking pail. He’d come with the aluminium pail and you used to have to empty your pail into the aluminium one. He’d come down and take two pail-fulls up to the house and put them over a freezer. There was a recess at the top and that used to hold a pail-full of milk. That used to come down and go over the top of water. This cold water used to run over top of like a radiator thing that’s how they used to cool it and that would go into 17-gallon churns that come up to a narrow neck and the top thick old lid. In the middle of the lid was a hand-hold, and you’d put your hand onto that and you could roll that up the yard easy as anything. They used to have to go onto the wooden stand on the side of the road where a lorry could pull up. They had to be there by eight o’clock in the morning. I’ve sat and milked 22 head of cows one after the other. Stick your old head into her flank and you’re away. There’s something nice about it. Girls would come from different houses after the milk, in the morning. I sometimes used to get the old teat and spray it their way! One or two of the old cows would kick or sometimes they put their foot into the pail – oh all sorts of things.6

Hire Purchase problem

We bought a little old stove from Charles Turner in Hingham7 an established firm who used to come round by horse and cart (later-on he had a van). He’d always come through Wicklewood and then to Deopham. He came through Deopham at six o’clock on a Saturday night. He used to sell all sorts: bootlaces, boot polish, haberdashery, paraffin and that sort of thing. We decided to get this little stove with one wick in it – three and sixpence it was. I think mother [i.e. Margaret, his wife] paid eighteen pence for it and then we paid sixpence a week. Well that got to the third week and we hadn’t got the sixpence! So we put the fire out, we put the candle out and we put the bar over the back door, and we hid up like a couple of little frightened mice! He banged and banged at that old door! He went round to next door and I reckon he asked, ‘What, are they out next door?’ They said, ‘They were there a little while ago!’ He came back and rattled and banged at the door and we sat there and we daren’t breathe! There we were married, and got a child and I was getting a man’s wage and we were frightened! We heard his old van go down the road round those ‘s’ bends, and we watched his lights go past the old man’s farm and we knew he weren’t coming back again after his sixpence.

From that day mother [Margaret] never owed anybody a penny. Even when she worked down at the shop all those years for Mrs Ruthven at Morley, if she wanted some stuff and she hadn’t got enough on her, she would go home and get her purse then come back to collect the stuff. She was working there but she never wanted to owe anybody.

Leaky Boots

I got a pair of horses on the six-acre field near Deopham School and I was ploughing up old sugar-beet land, ready for barley the next year. Water laid everywhere. I’d got my old boots on but my feet were sodden. I was trying to keep my feet warm but the water kept coming into the furrow as I went up and as I come back. As I turned, who should come up the road but the two women [Mrs Downes and Margaret, Jack’s wife] with their little prams. Just past the school you can come down there to Deopham church and go down to Kimberley Station, but mother avoided that ‘cos if they walked to Wymondham, it was a penny-ha’ penny cheaper to get the train to go to Norwich. I had a chat with the little old boy and said cheerio and they went off up the road. Mother [Margaret] was walking on the side of her foot. She’d been trying to patch her shoes up ‘cos they’d got holes in. She’d got an old bit of leather off my old boots and the bloody nails had come through! She was hobbling off to Wymondham to save a penny-ha’penny on the train. I don’t mind admitting, I cried. I thought, ‘what have we done to deserve this?’8

Parish relief

Jack commented on the lack of “dole” at that time, although there was “parish relief” available for some.

As you go from where I lived at Deopham towards Hingham there’re sharp ‘s’ bends, and there is a big grass verge with a hedge. Two or three men would bike there for half past six in the morning and stop there all day with their barrows and things working on the little hedges to make them better looking. They are there now, those hedges. They used to get six bob if they went for two or three days. That was parish relief. Wintertime, when we got snowed up – ‘cos we used to then they used to have to clear the snow and dig paths out, clearing anywhere that was snowbound. They’d get extra for that otherwise it was bloody hard.

They were hard times and it makes me sick nowadays, these young chaps of 45 and 50, they ridicule them and say I would have told them to get stuffed. I heard of that enough on the farm, and I used to say, ‘No you wouldn’t, if you’d got a wife and child, and a decent wage coming in, you’d keep your mouth shut.’ They just cannot take that in. It grieves me sometimes to hear. You see you can stand up now and argue with your employer – in fact he hardly dares argue with you! It’s got out of hand.

Extra work

At Christmas, Jack looked for extra opportunities to earn more.

It was getting towards Christmas and I was getting a bit desperate then. You wanted a bit extra for Christmas. Then old man Peacock he say to me, ‘If you want to earn a little extra for Christmas you can go and mould up the two heaps of mangolds on that six acre.’ Well, you see, that was on the six acres on the bottom field at Deopham. They used to cart the mangolds and heap them up, but because mangolds are full of water, if you got a frost on them they wouldn’t be any good. So you used to have to straw them and then dig a trench round the bottom of the heap and then you’d put a foot of mould on. He found me a hurricane lantern! You’d dig a trench about a yard wide and I’ve known him to walk through there and he’d put a stick in where I had patted the mould to see that I hadn’t put a thin layer on.

Then three weeks afore Christmas you’d go a-plucking. Clarkes (?) in the village they had turkeys, and I used to sit there until two o’clock in the morning plucking turkeys. You used to have a ladder and you’d tie them up. Then they would pick them up at five o’clock the next morning and they’d go off to where they sold them. Fifteen shilling I earnt one Christmas. Then one year Cecil Matheson (?) – he was in poultry – he made a bargain. When I went home to tea at night there would be two or three crates of chickens standing by the old shed ready for me to pluck and truss. I could pluck them at home and then he’d pick them up at four or five o’clock in the morning and take them off to the station. That saved me running about. Then always, whatever I earned extra above my wages, I’d go 50/50 with mother [i.e. Margaret, his wife].9

Working with Bob Flint doing the threshing was not comfortable:

I used to carry 18 stone of corn off the back of the cart into the barn and set it up high against the wall – big old sacks. Them old corn sacks when they tied them up they had a bit to spare out of the top and you’d pull it over so when you set the other one on that would be set up straight and tidy. Eighteen stone of wheat, 16 stone of barley, 12 stone of oats, 24 for linseed. I’ve gone home at night and I’ve cried when mother [Margaret] has peeled my shirt off my back. I had to go back the next day, and I can feel it now, getting up against that first bloody sack and I’d hardly dare put it onto my shoulders. My skin was raw – I’ve cried. Calamine lotion – weren’t that lovely to feel over your back? You knew you’d got to go the next day and I wouldn’t give in. It was only my headstrong determination kept me going. Times were hard – do you know we used to sit back to back to eat our dinner – that way we rested our backs. You had to, it was bloody hard work in them days.

Tractors

Whilst working for William Peacock, Jack started to work with tractors. He recalls that he drove a “Fordson with no mudguards, and spiked wheels” such as the following:

Reproduced with permission from H. J. Pugh & Co

The track rod on this tractor would snap fairly frequently and would then have to be taken to Gerry Reeves in Attleborough to be repaired:

Of course there wasn’t no such thing as welding as we know it now, but he used to get these two bits and they’d measure them and get the chalk mark on them. They’d get the two ends white hot, two of them, and they would hammer them together. That old track rod got full of knots and bumps but they had to get it as right as they could. It was always breaking because of the vibration from the tractor with the heavy old wheels – I’m talking of 60 year ago.

One Monday at the back of the farm near the school, the track rod snapped and I had to take that to Attleborough. Well Myrtle, (Lidlaw’s daughter) she’d got a car, big old square type brown Austin – that was in the garage round the back of the farm. It was Monday, washday, and the old man he say,

‘I daren’t ask her to go as it’s washday. Jack, what are we going to do?’

‘Well,’ I say, ‘I shall have to bike in with it.’

He say, You can drive a tractor – can’t you drive that old motor?’

So we crept round there and undone those doors right quietly and we pushed that motor down onto the road towards the shop, so Myrtle couldn’t hear us. We started it up and off I went to Gerry Reeves. Weren’t I King of the Castle – weren’t I somebody! I drove into his little old drive and messed about waiting for it to be done. Well, Percy (Myrtle’s brother) had his farm just up the road, and he’d come into Attleborough for something, only to see the car stand there! So he come to see what was going on. He say, ‘Where’s Myrtle?’

There was a hell of a do then! Myrtle had to bike in and put her bike in the back and take it home again. I hadn’t got a licence, had I? Three or four days later a little red cardboard thing come through the post – that was my driving licence! I never had to take my test. I got what they called a ‘grandfather’s licence’. All you had to do was sign a paper to say you’d been driving that type of vehicle so long and you were quite capable, and that was enough.10

The following picture is of Myrtle Peacock surrounded by turkeys:

Thanks to Elaine Peacock for sight of this photo.

First driving licence

I got my first driving licence in 1937, which was when I was at Peacocks at Deopham in that little old cottage. I had the first tractor around there – an old Fordson with no mudguards, and spiked wheels. It had a double-furrow plough, on wheels. There was a four-acre field opposite Deopham ‘Half Moon’, down at Pettengills Farm. I’ve been in there with the tractor and plough, working for different farmers. Mr Dring with his pony and cart and Mr Bales on his bike watching me plough up and down in that field.11

1939

The 1939 Register recorded John and Margaret Juby living at High Elm Cottages (subsequently named Keeper’s Cottage) and his occupation was recorded as “Farm Labourer”.

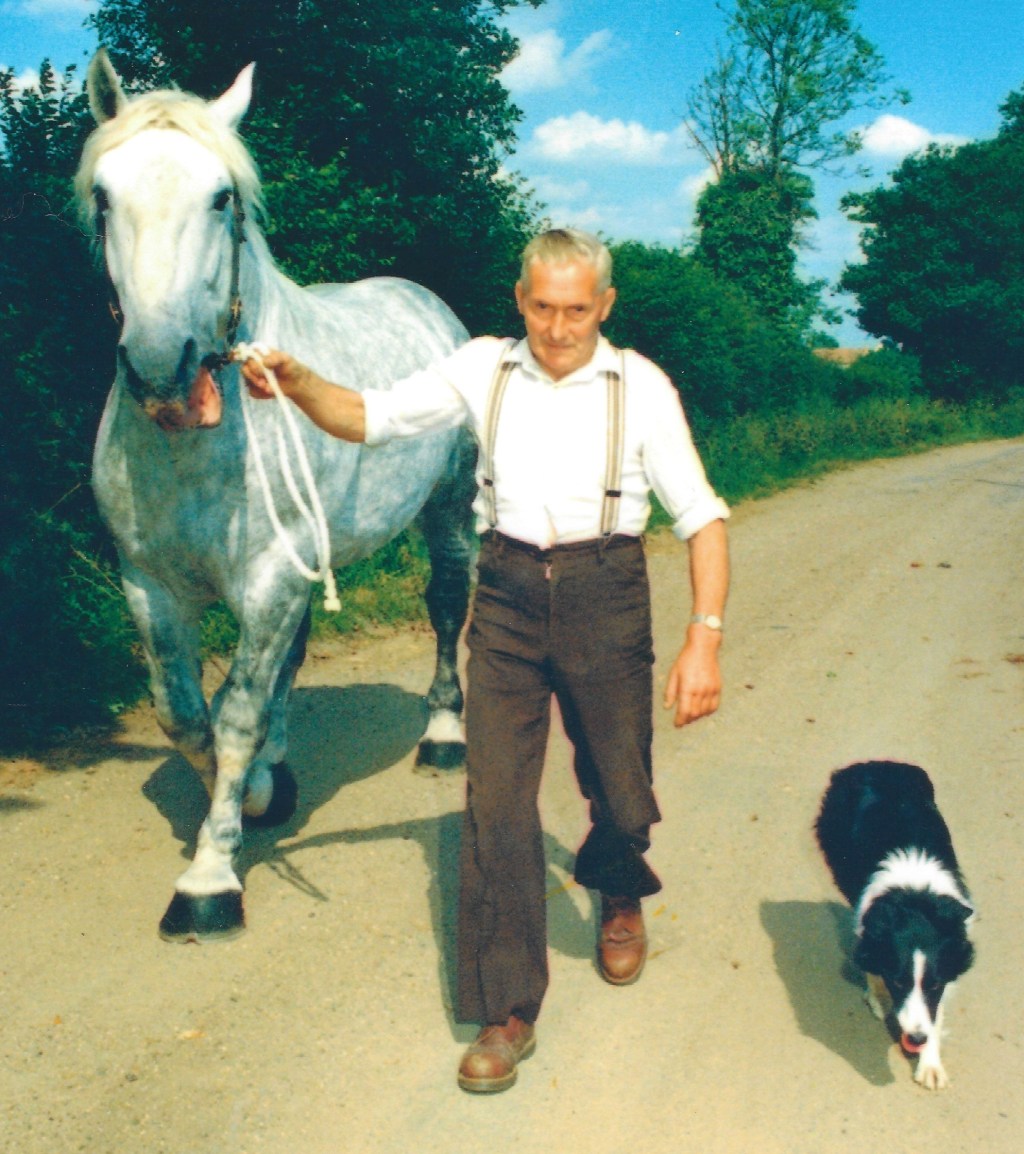

Walking the Stallions

It was whilst working for William Peacock that Jack started to “walk the stallions”. This involved taking a stallion around the farms by prior arrangement to cover the mares. This meant that he was away from home Monday to Friday, leaving on a Monday “with the pony and cart loaded with my grub, and chaff and corn for the horse underneath, and the little old dog beside me”.

On one occasion, his wife met a lengthman (someone who keeps a length of road in good repair) that knew Jack whilst she was in the village shop at Bawdeswell; this man tried to wind her up, as Jack recounts:

‘What you keep coming home for like this?’

‘Well,’ she says, ‘my husband is away all week, so I’m on my own’. She let it out that I travelled the stallion around that way you see, and stayed out at nights. ‘Oh,’ he say, (that old bugger, he done it on purpose) ‘I know him – I know who you’re a-talking about. He come this way. He done that way last year and they reckon he left more foals than what the stallion did!’ That got a laugh for years after. The stallion leaders were notorious for it, and they got a bad name for that.

Although more lucrative than basic farm work, stallion walking was very competitive and the grooms had to earn their keep:

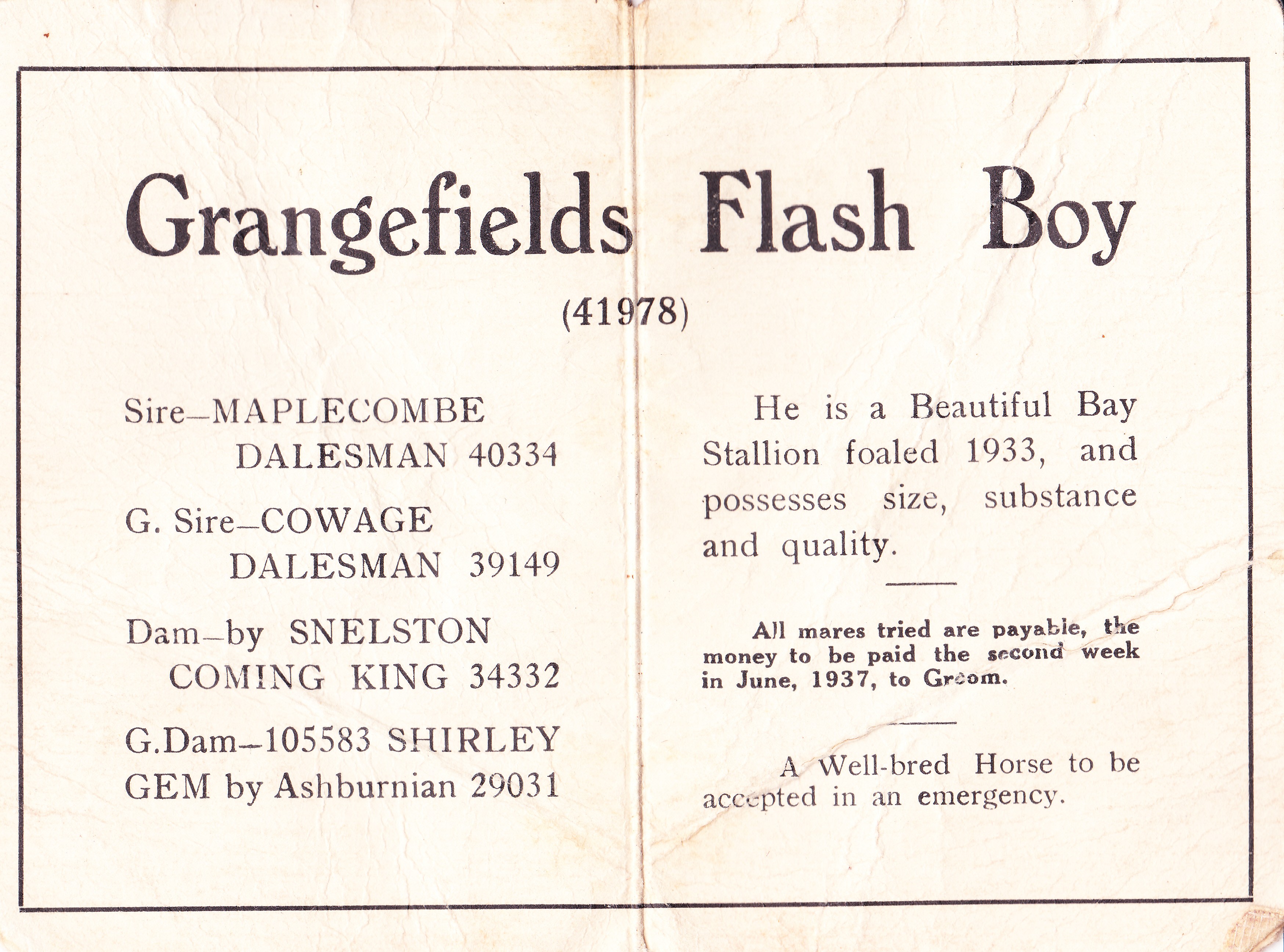

On Dereham market place on a Friday there would be seven of us the first week of the season, the horses all braided-up and plaited-up, and with a pocket-full of cards with details of the name of the stallion and where you were going to stop at certain nights. The farmers would look round them – you’d walk them up and down. Then we used to go into the ‘Bull’ and feed the horse, and in the afternoon you’d go up and down again.

There were three Peacock stallions at this time12:

| Stallion | Walked by | Owned by | Area covered |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pettengills Grey King | Jack Juby | Percy Peacock | Dereham & Fakenham |

| Flash Boy | Charlie Skipper | William Peacock | Watton |

| ‘Old Sugar’ | Geoffrey Peacock | Forncett |

Jack refers above to having a pocket-full of cards to hand out at the market. These would have been like the following examples:

With thanks to Elaine Peacock for sight of these cards.

Wartime

Jack recalls one wartime episode when he and the dog had been unable to get accomodation in a pub, although the horse was given stabling. He therefore turned his cart upside down, and then Jack and the dog slept under it. He said that this was …

A terrifying experience – each bomb seemed nearer, and the last one set the walls vibrating and started the cart wheels revolving, which they continued to do for an incredibly long time. The horse snorted a bit but it was surprising how he accepted the situation.

Shows

The first show I ever went to, to show horses, was at Beccles. I was about 16 or 17. I shew for Geoffrey Peacock – that was old Captain, a Percheron, in a single wagon. The things were not so up to date then. We had got a good set of harness then, but not like they are now. There weren’t the number of classes and things. I remember Captain, he had got bad old feet, with great cracks, and we patched it all up with soap to fill in the cracks, and they looked alright time he was in the ring! But of course you don’t get that today because different societies started getting classes for the best feet, and that improved people looking after the feet. ‘Course some of it was caused through neglect and some through the breeding. That’s why I used to cut the hoof down to get rid of the old. You can’t grow a new hoof until you have got rid of the old. You see, they get a lot of pressure on the new bits if you haven’t got rid of the old.13

Departure from Deopham

William Liddelow Peacock died on May 23rd 1942. Jack decided then at the age of 22 that it was time for him to move on from Deopham. Initially Joe Bales (also known as Fred Bales, who farmed at Ivy Farm, Deopham Green) helped him find work in Tittleshall, but this did not work out and he found work at Cranworth where he remained for over three years.

Jack worked on a number of farms around the area including Cranworth, Marsham, Stody Hall and Upton. His experiences there are detailed in his daughter’s book. He gained a well respected reputation for his knowledge and affinity with heavy horses.

Return to Peacocks

Eventually, around 1960, Geoffrey Peacock invited Jack to work at Lime Tree Farm in Morley where the Peacocks provided the Juby family with a house. Jack cared for the Peacock Percheron horses for which they were renowned worldwide; Jack prepared and exhibited the Percherons at shows – notably the Royal Norfolk Show.

Although based in Morley, there are still local residents who remember receiving invaluable advice from Jack Juby about caring for their horses.

Photo: Alison Downes, January 1993

2001

2001 was a year of mixed fortunes. Following the death of Roger Peacock, Lime Tree Farm in Morley had to be sold. Roger Peacock was the fourth generation of the Peacock dynasty that Jack worked for. Jack and his wife Margaret had to leave Morley so they moved to what was to be their retirement home in Hingham.

The fear of the workhouse was something inextricably linked with the tied farm cottages, even at this time of his life. Alison Downes has explained that Jack was constantly aware that he could be asked to leave his tied homes at a moment’s notice: he had no protection.

On November 9th 2001 he received news from Downing Street that his name was going to be put forward to Queen Elizabeth for inclusion on the New Year’s Honours List for his “services to heavy horses”. In particular, this was for his work in breeding the Percherons.

Unfortunately, ill-health prevented him from visiting Buckingham Palace to receive his M.B.E.: it was presented to him by the postman.

Death

Jack Juby died on March 30th 2004 in the Priscilla Bacon hospice; his funeral took place at Morley St. Botolph church, where his coffin was transported on a cart pulled by a Shire horse. Jack was buried in the churchyard at Hingham. His headstone, a short way back from the road, shows a heavy horse pulling a hay cart. A collie is standing alongside:

Photo: G. Sankey, October 2024

Photo: G. Sankey, October 2024

Alison Downes has said that the one quote above all others that Jack would want to be remembered by is:-

“I’ve loved every day of my life.“

Footnotes

- My Life with Horses, The Story of Jack Juby, MBE, edited by Alison Downes and Alan Childs, Page 39 ↩︎

- Ibid, Page 38 ↩︎

- Ibid, Page 34 ↩︎

- Ibid, Page 39 ↩︎

- Ibid, Page 40 ↩︎

- Ibid, Page 43 ↩︎

- Charles Turner started his career as an assistant at Clarke’s and by 1888 he owned the business. In 1914 Charles described himself as a dealer in hardware, ironmongery, groceries, earthenware, tobacco, boots and small wares. At the back of the premises was a small warehouse where up to 20 lb of gun-powder was stored; across the yard were buildings used for storing a lorry and van with paraffin and 100 gallons of petrol. Charles Turner died in 1941 and three of his children, Ted, Tom and Gertie carried on the business until Ted was over 80 years old.

Extracted from: hinghamhistorycentre.co.uk ↩︎ - My Life with Horses, The Story of Jack Juby, MBE, edited by Alison Downes and Alan Childs, Page 44 ↩︎

- Ibid, Page 45 ↩︎

- Ibid, Page 47 ↩︎

- Ibid, Page 46 ↩︎

- This table was derived from information in My Life with Horses, The Story of Jack Juby, MBE, edited by Alison Downes and Alan Childs, Page 56. ↩︎

- Ibid, Page 57 ↩︎

Credits

I am indebted to Alison Downes’ book (details in the Bibliography below).

I also appreciate the help received from Martin Abel in drawing attention to this story.

Bibliography

My Life with Horses, The Story of Jack Juby, MBE, edited by Alison Downes and Alan Childs, published 2006

[Alison Downes is Jack Juby’s daughter]

Navigation

| Date | Change |

|---|---|

| 3/4/25 | Further comments from Alison Downes |

| 31/3/25 | Revisions from Alison Downes |

| 11/3/25 | Note on Joe Bales |

| 8/3/25 | Published |